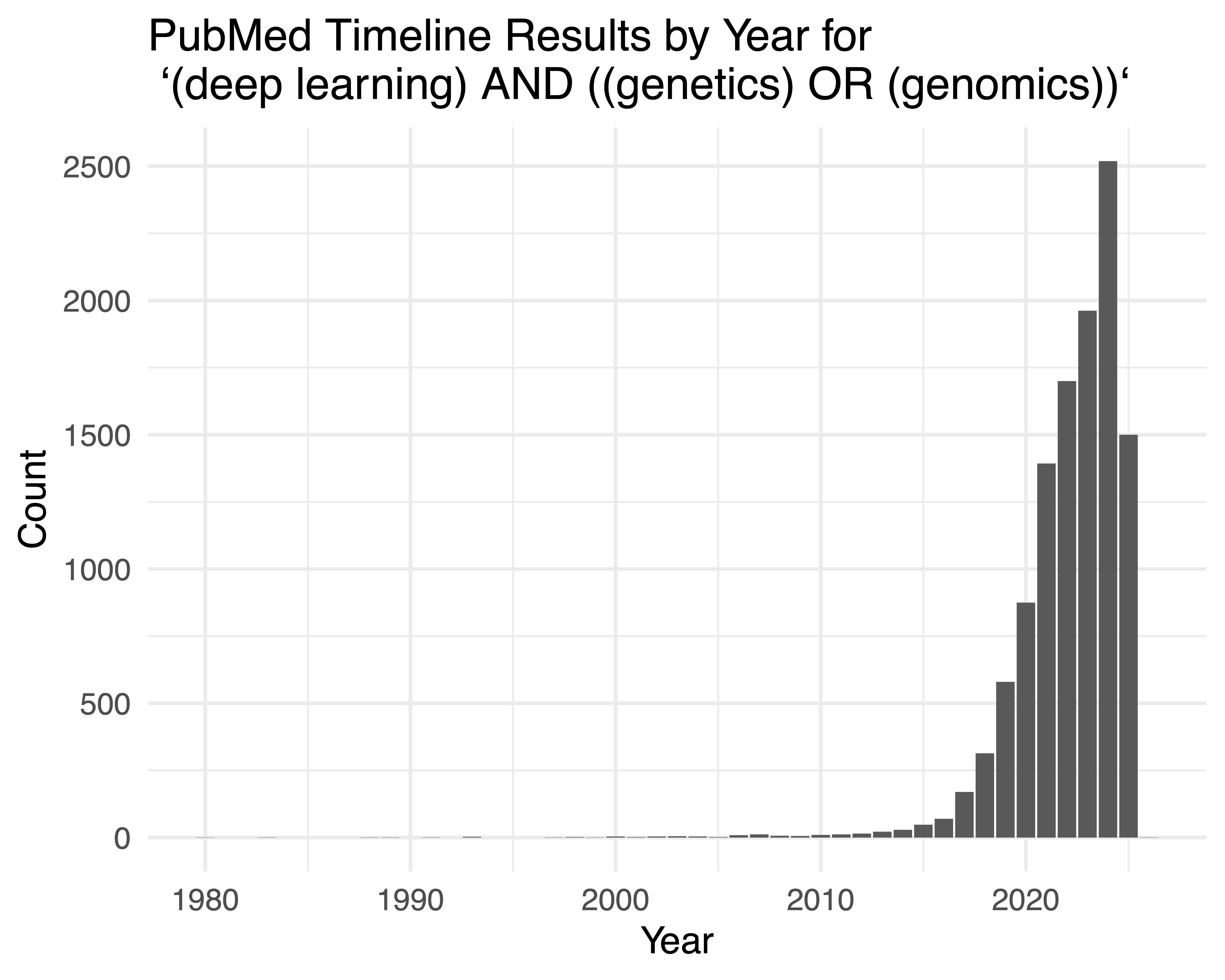

With the rise of large genetic and genomic datasets, an important challenge is how to leverage these data to better understand how genetics and genomics contributes to human disease. Historically, machine learning and statistics have been used to infer associations or identify differences in genomic data, to build predictive models, and to identify genetic elements important to disease and cellular processes. Most recently, there has been great progress made in leveraging core ideas from deep learning to solve important and open challenges with these data. For example, a search on PubMed for (deep learning) AND ((genetics) OR (genomics)) in June 2025 shows great interest in these topics (Figure 1). One challenge we face as educators and instructors is how to translate the fast-paced world of research at the intersection of deep learning and genomics to the classroom so that we can discuss both the historical context of these models along with their performance and applications to large genetic and genomic datasets actively being generated today.

(deep learning) AND ((genetics) OR (genomics)). The data were downloaded and a barplot was made with ggplot2.

Towards this goal, we recently developed and taught a graduate-level discussion-based course titled “Advanced Topics in Genomic Data Analysis” in Spring 2025 at the Whiting School of Engineering at Johns Hopkins University (EN.580.743.01). The purpose of this post is to provide an overview of the course structure, a description of the papers that were used in the Spring 2025 course, and reflections on the course afterwards. Our goal in writing this summary of the course is to help inspire other instructors to develop similar courses at their own universities and institutions so that students there can bridge both the historical context of these deep learning models and be able to critically discuss and assess their applications to large datasets today.

Prerequisites

Because this course was designed to be a discussion-based course, we asked students interested in enrolling to describe their background and experience with genomics and machine learning. While there was diversity in the home departments and the types of genomic data that the students had prior experience with, almost all of the students who ultimately enrolled had firsthand experience in applying machine learning or deep learning models to genomic data. In addition, we designed the course to be a graduate-level course with a primary target population of PhD students. However, we were inclusive to a range of levels including undergraduate students with strong research experience in these topics. Finally, while we did not have required textbooks, we suggested supplemental reading materials including Molecular Biology of the Cell, An Owner’s Guide to the Human Genome, An Introduction to Statistical Learning, and Deep Learning to help fill in potential gaps ranging from molecular biology, human genetics, statistics, machine learning, and deep learning.

Course expectations

A key component to the success of the class was to clearly describe the course expectations to the students from the start. On the first day, we described to the students the course expectations which were that students will present and lead class discussions on papers in the current literature. In addition, students would also complete two small pre-defined analysis assignments using publicly available data, in addition to a final project of the student’s choosing. In terms of the number of presentations to give, we asked students to sign up to give presentations for two papers as a primary presenter and for two papers as a secondary/supporting presenter. The purpose of this was to ensure that each paper had at least two presenters so that they could discuss the paper with each other if they had questions about it. The number of presentations we asked students to participate in as a primary or secondary presenter was a function of the number of days we met over the course of the semester along with the number of students enrolled in the class. In our class, we met twice a week over the course of a semester. To leave room for final project presentations at the end, we planned for 24 presentations over 12 weeks, including the first day where we gave an overview of the course. Finally, all students were notified that they were expected to read the papers in advance of the class and be prepared to discuss and ask questions as the papers were being presented.

Grading criteria

Another goal on the first day of class was to describe what the grading criteria would be. The breakdown of the grading was the following:

- Discussion presentations: 25%

- Attendance and active discussion and participation: 25%

- Two small pre-defined mini-assignments using publicly available data: 30%

- Final project of the students’ choosing (working either alone or in a group of two): 20%

Because this was a discussion-based course, we expressed that class participation was a major component of the final grade, even for students auditing the course. For students who missed a class due to illness or some kind of necessary conflict, we asked students to send questions to us after class related to something they noticed or were confused about when reading the paper.

Papers discussed

We carefully selected papers to cover a broad range of topics ranging from foundational concepts in statistical genetics and functional genomics to more modern deep learning algorithms including transformers and deep generative models. For each lecture, there was a primary paper that the students were asked to present, but in some cases there was a secondary paper (either a supplemental reference or different paper also relevant for the discussion). Below is a list of papers that were discussed. For the “wildcard” module, we asked students to vote amongst themselves to select a topic for discussion.

| Lecture | Module | Primary paper | Secondary paper |

| 1 | Introduction | Course overview – presented by instructors | |

| 2 | Statistical Genetics I | Statistical significance for genomewide studies (link) | Genome-wide association studies (link) |

| 3 | Interpreting principal component analyses of spatial population genetic variation (link) | New approaches to population stratification in genome-wide association studies (link) | |

| 4 | Common SNPs explain a large proportion of the heritability for human height (link) | – | |

| 5 | Deep Learning I | Deep learning: new computational modelling techniques for genomics (link) | – |

| 6 | Transformers in single-cell omics: a review and new perspectives (link) | – | |

| 7 | eQTLs and Sequence to Function models | Molecular quantitative trait loci (link) | The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues (link) |

| 8 | ChromBPNet: bias factorized, base-resolution deep learning models of chromatin accessibility reveal cis-regulatory sequence syntax, transcription factor footprints and regulatory variants (link) | Effective gene expression prediction from sequence by integrating long-range interactions (link) | |

| 9 | Decoding sequence determinants of gene expression in diverse cellular and disease states (link) | Deep-learning prediction of gene expression from personal genomes (link) | |

| 10 | Deep Learning II | Enhancing scientific discoveries in molecular biology with deep generative models (link) | – |

| 11 | Obtaining genetics insights from deep learning via explainable artificial intelligence (link) | – | |

| 12 | Functional Genomics | Deep generative modeling for single-cell transcriptomics (link) | Assessing the limits of zero-shot foundation models in single-cell biology (link) |

| 13 | Transfer learning enables predictions in network biology (link) | – | |

| 14 | Spatially informed clustering, integration, and deconvolution of spatial transcriptomics with GraphST (link) | – | |

| 15 | Integrating spatial transcriptomics data across different conditions, technologies and developmental stages (link) | – | |

| 16 | Other timely ML applications | HyenaDNA: Long-Range Genomic Sequence Modeling at Single Nucleotide Resolution (link) | – |

| 17 | Predicting transcriptional outcomes of novel multigene perturbations with GEARS (link) | Deep learning-based predictions of gene perturbation effects do not yet outperform simple linear baselines (link) | |

| 18 | SVision: a deep learning approach to resolve complex structural variants (link) | – | |

| 19 | Small-cohort GWAS discovery with AI over massive functional genomics knowledge graph (link) | – | |

| 20 | Statistical Genetics II | LD Score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies (link) | – |

| 21 | Incorporating functional priors improves polygenic prediction accuracy in UK Biobank and 23andMe data sets (link) | Modeling Linkage Disequilibrium Increases Accuracy of Polygenic Risk Scores (link) | |

| 22 | Trans Effects on Gene Expression Can Drive Omnigenic Inheritance (link) | – | |

| 23 | Wildcard | Patenting Genes: What Does Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics Mean for Genetic Testing and Research? (link) | Clinical utility of polygenic risk scores for embryo selection: A points to consider statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) (link) |

Mini-assignments

The course consisted of two mini-assignments or projects in the first two thirds of the course. The purpose of these assignments were to practice both writing code and narrative text related to the papers we discussed in class. For the coding portion, a skeleton of a jupyter notebook was provided as a starting point. The first mini-assignment practiced using the tensorQTL package for extremely fast QTL calling and the second-mini assignment practiced using scVI for batch integration with single-cell RNA-sequencing data. In terms of the writing portion, students were asked to pick two papers that we read in class (any paper up through the due date of the assignment) and write an alternative introduction (not the abstract), which should include introducing the topic and the importance of the paper (roughly 6-10 sentences). The purpose was to practice re-writing the introduction for different audiences. For example, pick an introduction that appears to target a broad audience and write new introductory sentences as if you were targeting more specialized experts in the topic of the paper. For the second paper, the student was asked to do the opposite. Finally, we also aimed to have each student practice writing a “Methods” section by picking a paper we read in class where they thought the methods were unclear and requiring them to re-write a key piece (1-2 paragraphs) of the methods section. It should be noted that we were not penalizing right or wrong answers here, but rather we aimed for students to improve their writing of details.

Final project

The final project was to use machine learning to address a problem in biology/genomics. In terms of topics, there were two options:

- Using a published paper with publicly available data, replicate 2-3 key results from the paper that used machine learning or statistical approach in application of genomic data and extend it with at two additional, related analyses (i.e. 2 figures) of your own that would be interesting such as:

- Comparing their method to an additional baseline not shown

- Testing with a different performance metric

- Modifying their approach in some way and showing results with that

- Additional exploration of results such as different visualization, gene set enrichment analysis or other biologically-revealing analysis.

- Apply a machine learning method to a particular biological problem or dataset and evaluate its performance in comparison to a baseline approach. There should be some aspect of novelty:

- A “twist” on an existing machine learning method

- Results that provide new insight into a biological question

- Application of a method to a data type or problem to which it has not previously been applied

We encouraged individuals to work in groups of 2 people, but students could also complete the project on their own if they preferred. The project could have overlap with research in a lab, or with any other project, but we just asked students to state which parts of the project were specifically for this class. In terms of scope, we strongly encouraged projects that could be completed in the time available. For example, the project was primarily intended to practice with public data and explore existing machine learning algorithms, but it could potentially lead to a larger research project going forward beyond the class.

In terms of deliverables, there were three components required for the final project, each with their own due dates. The deliverables were a (1) set of “specific aims”, (2) a final project presentation given in class, and (3) a final write up of the methods and results including source code, a link to the data, and a statement describing any potential overlap with ongoing research projects outside of class. We prioritized asking students to make their code reproducible, including all steps of your analysis from preprocessing to producing final figures and results shown in your writeup.

The specific aims page should be 1 page in length and follow an NIH-style specific aims page in terms of other format requirements, not the scope of the project. For the final project presentations, we asked students to sign up for a 10-15 minute presentation in class over the course of two classes. Students were not expected to have finished the project by the project presentation, but the presentation needed to contain meaningful results. The presentation also allowed us to provide feedback before the final project writeup was due.

Recommendations for future versions of the course

Looking forward, we hope to build on the success of this course, with an eye toward further improving the experience and impact for students. Key considerations are course content, logistics, and discussion management. The content, including the broad topics and papers selected, was a highlight of the class in the last iteration. We hope to maintain the mix of foundational and cutting-edge papers, and recognize that this will require refreshing the list regularly to keep up with the fast-moving field. Logistically, the class size of 10-20 students was close to optimal, balancing lively discussion where everyone could participate, without being so small that each student had to lead the discussion too often. Relatedly, the diverse make-up of the class, covering a range of backgrounds and degree programs, was a benefit, where some students could help explain detailed statistical methods, and others could provide insight into biological mechanisms or motivations. Areas for improvement in the course logistics include providing students with additional example materials: sample successful projects, examples of strong discussion lead presentations, and very clear information about grading criteria.

The final area for consideration is how to maintain active, interesting, and thorough discussions of the material. Providing example discussion presentations will help kick things off in a good direction, demonstrating the need to cover methods and results and to raise probing questions and discussion points. We find, however, that it is also important throughout the course to keep an eye on discussion and participation, to chime in occasionally when discussion dies down, and remind participants and discussion leaders of their roles, or gently call on students who are not participating. Finally, it is absolutely essential to make sure students feel encouraged to have a very open discussion without judgement, and that they can ask questions that may feel silly, reveal a lack of understanding, or alternatively may be critical of a published paper’s content or writing style. Cutting edge papers can be hard to understand, controversial, and even occasionally have mistakes.

Final comments

We found this class engaging and fun to teach, and also learned more about the field ourselves throughout the semester. We would love to hear feedback, suggestions for topics and papers, or questions.